While The New Creature Canon is specifically meant to cover lesser-known or offbeat monster stuff, every once in a while I get interested in writing about certifiable classics. Last year, I wrote about a few just on a whim and folded them into NCC, but starting with this, some of the more well-known or celebrated subjects will be featured in their very own monthly (maybe? Hopefully?) series.

I didn’t plan on watching Shin Godzilla and the 1984 movie version of Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind on the same day, and it was probably only about halfway through the latter when I realized what an appropriate double feature it was. The direct connection is obvious to everyone who knows about those movies’ histories: Shin Godzilla co-director Hideaki Anno (known mainly as the creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion) got his start in the animation industry working on Nausicaä, being specifically tasked with animating the sequence featuring the giant God Warrior, a melting, corpse-like entity that would prove to be one of the (many) iconic elements of the film. Three decades later, Anno produced a live action short film depicting the God Warrior attacking Tokyo for a museum exhibit on tokusatsu that used a combination of classical and digital effects (I’d link to it, but no complete version of the original exists online), which likely had a large influence on the making of Shin Godzilla a few years after that.

But it’s also clear that his work on Nausicaä had a much deeper influence on the movie: in Shin, Godzilla is as much like Miyazakis’ God Warriors as he is like previous incarnations of Godzilla, both in his visual depiction—less like a giant animal and more like a sickly aberration, scabbed, gelatinous flesh in his earlier “unfinished” stages, and something like a molten tumour with ungainly proportions in his final form—and in his behaviour, which seems borderline mindless, the destruction he causes often coming off as just a mechanical reaction to what happens around him. Even his trademark radiation breath looks very similar to the hyper-destructive beams fired by the God Warriors. Both are meant to represent the worst abuses of the natural world by human hands, but the simpler allegory of the older Godzilla films (which took inspiration mainly from movies like King Kong) has been usurped by the coarser and angrier one pioneered by Miyazaki in his story, which feels increasingly appropriate as we’ve had further decades of thoughtless environmental abuse. It wasn’t enough for us to accidentally create a giant monster in these stories: the giant monster has to look like Death Itself to get the point across.

That unexpected thematic two-fer only reinforced a notion I’ve held for a while: while both the manga and animated versions of Nausicaä are rightly regarded as seminal, and are highly influential to the entirety of Japanese pop culture (you wouldn’t have the world design of many video games without it), they are also innovators specifically in the realm of monster stories, providing some of the most memorable creatures of all time, and making them a central part of the narrative’s thematic core. Not since the original Godzilla had giant creatures, and how they relate to mankind, been taken that seriously—and very rarely have they ever been made to feel a wholly organic part of their universe.

Nausicaä is, of course, about the titular princess of the Valley of the Wind, a clean and peaceful land in a version of Earth that went down in nuclear flames a millennia before in an event called the Seven Days of Fire, and has managed to rebuild itself into a semi-medieval society with access to some impressive (and also amazing-looking) pieces of technology, from Nausicaä’s glider to the massive flying warships used by the militaristic Torumekian kingdom. Part of the reason the Valley of the Wind is such a nice place is that the gusts in its name keep away the spores of the Sea of Corruption, a spreading forest of deadly plants and fungi inhabited mostly by insects, such as the massive worm-like Ohmu, and deadly to every other form of life. While many of the humans view the Sea of Corruption as a danger that they must solve (while getting into conflicts with other human civilizations over diminishing resources), Nausicaä is highly curious about how it functions, and in the process of investigating it (in both the early parts of the manga and the film, which is truncated adaptation of those early parts), discovers that it is actually purifying the land that had been polluted by the previous civilization (read: ours.) Her quest to share her discovery and broker peace between the warring factions is the primary plot of both the manga and the film, with the former (which ran in a stop-start fashion between 1982 and 1994, Miyazaki having to put it aside every time he directed another movie) going even deeper into the complexities of the world and its history. Along the way, we are introduced to many outstanding creatures that fully embody both humanity’s capacity for natural devastation, and a cooperative path to something better.

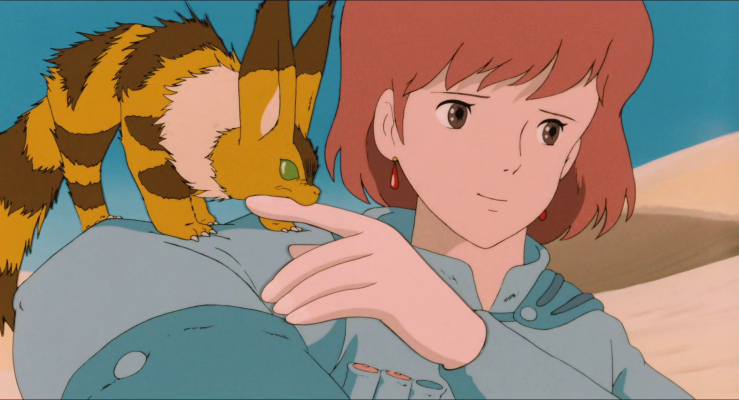

Nausicaä’s empathy towards all living things and her close bond with several of them is one of key ways she demonstrates her heroic nature, and a path towards harmony. She is accompanied by her pet squirrel-fox Teto, one of the first adorable mascots Miyazaki and his Ghibli cohorts created in what would become a long list of them, and often rides around on the ostrich-like Horseclaws (which are blatantly the basis for Final Fantasy‘s chocobos.) Her lifelong respect for the Ohmu, viewed by most other humans as a menace, and her attempts to protect them (especially in the scenes where the Torumekians drag around a baby Ohmu in order to lure a herd) is one of the vital moments of the story, the point where she is shown to be a intermediary between man and nature, and taking on the saviour role that defines most of her subsequent actions.

While the God Warriors—bio-engineered monstrosities that were responsible for the Seven Days of Fire—represent the endpoint for our near-suicidal disregard for the well-being of our world (and so the attempts by the Torumekians to revive one of them as a defence against the Sea of Corruption becomes an example of not learning from history), the Ohmu are their opposite, things that are in many ways just as scary and just as capable of mass destruction, but only doing so in order to protect the natural course of things, a process that is in fact healing the Earth in the long term, even if it makes things difficult for us in the short. On the surface, one is a man-made disaster, the other a natural one (which is the dichotomy that has always existed in the giant monster genre from its earliest days)—although, as we learn in the manga, the distinction is much blurrier—and while both spell bad news for everyone in their path (Miyazaki never downplays the struggle for survival), the latter one at least has the possibility of fulfilling a role in the natural cycle, rather than only bringing death. The massive, utterly alien-looking Ohmu should really be considered among the best monster designs of all time, simple in concept but fully capable of fulfilling both roles as both kaiju-style destroyers and benevolent guardians of nature—and in the film, the animation of their segmented movements is astounding-looking even to this day, as is the animation of the half-formed God Warrior.

The manga expands on the ideas presented in the movie, creating an even more complicated picture of the planet’s future and just what role humans play in it, and introduces even more creatures along the way. Probably the single most terrifying thing in the entire story is the engineered mould unleashed by the Dorok Empire (who descended from the scientific minds that created the Sea of Corruption), which spreads uncontrollably and causes untold damage before it is halted by the Ohmu—compared even to the God Warriors, it is the most violent expression of just how badly we can screw up when we don’t think these things through, creating a spreading disaster that dwarfs even giant-sized monsters (Miyazaki would later utilize similar imagery for the wave of pestilence unleashed by the Forest Spirit in Princess Mononoke.) The manga also includes the Heedra, the bulky, inhuman servants of the Dorok emperors, that are also genetically engineered—as are both the brother emperors, who use arcane science to obtain a form of immortality. But, while their aberrational nature is made quite clear in the text, even in the case of these manufactured organisms, Nausicaä demonstrates a high level of sensitivity, saying of the mould “I’ve never encountered so wretched a creature…Any form of life knows joy and satisfaction…But they know only hatred and fear…”, showing sympathy for this thing that never asked to exist. This ability to empathize with even those beings is important at many points in the manga especially, with the apex being Nausicaä becoming the “mother” of the revived God Warrior, who she names Ohma, and who she remains with for the rest of the story despite knowing that the radiation that it exudes kills everything around it. Her growing recognition of the complex interplay of all these things, man-made and natural, past and present, further tests her sense of purpose and her opposition to the fatalistic alternatives presented by other characters, making her final decision on the future of mankind at the end of the manga all the more thought-provoking.

Although the manga does indeed go much farther than the film and is therefore an even richer experience, both versions of Nausicaä represent some of the most intelligent use of the giant monster concept in any piece of fiction. Like the best giant monsters, the creatures are about the ideas behind them, of the uncontrollable things in our reality (whether they be natural or something we inadvertently concocted in our bid to control the natural), rather than just bringing a massive scope to the story. The Ohmu, the God Warriors, the mould, and other things in the narrative seem to be overwhelming, unmovable—but they, like us, are only part of a greater ecosystem, and humans themselves can have an outsized influence on that ecosystem as well. How we choose to intervene, and the points where we simply let nature take its course, will be the final arbiter of how that ecosystem moves on, and whether we’ll still be part of it.