In my last Creature Canon post, I briefly touched on my childhood interest in folklore and mythology and how seeing the things I was learning about reflected in the wider culture was a unique thrill—it was an ever-expanding world of fantastical stories and bizarre monsters that felt endlessly rewarding. I’m not entirely sure what put me on that path to begin with, whether it was seeing references to mythology in video games like Final Fantasy or even Pokémon or finding books solely about mythological creatures in the school library (my parents even bought me a massive encyclopedia of Greek, Norse, and Celtic myths at that time), since those things overlapped and fed into each other, and when the Internet came into the picture, that put the whole thing into overdrive. Whatever the real originator of my fascination was, it is still very clear that that stuff can really hook a kid, especially when presented in a way that emphasizes the adventurous and strange nature of those stories and avoids the stuffy academic version of it that may make the youths think Beowulf is just a musty old poem and not the tale of a guy who rips a giant monster’s arm off.

Kids’ innate interest in the creepy creatures of legend has been exploited in pop culture off and on for decades (most of the books I read on the subject were clearly aimed at that demographic), but an interesting example of it from the early nineties were the Monster in My Pocket toys produced by Matchbox and Morrison Entertainment Group, if only because of how direct it was in marketing hordes of mythological monsters as something cool. Clearly taking inspiration from mono-colour collectible mini toys like M.U.S.C.L.E (which were imported Kinnikuman figures, a subject that, because I’m me, I’ve broached before on this site) that had been popular in the eighties, MiMP came out in 1990, burned brightly for a year or two, and then disappeared off the face of the earth (except, apparently, in some parts of Europe, Central, and South America, and likely thousands of yard sales and flea markets), a veritable micro-phenomenon. Its business strategy was based on tried-and-true methods that still work to this day, cajoling kids into wanting to get as many possible (an early practitioner of “Gotta catch ’em all”), not just by offering a wide selection of different toys in blind or semi-blind packages and then making multiple colour variations of each one, but also by assigning them a “value” (here, a point system printed on the figures themselves) that serves no purpose but to make certain figures seem rarer or better than others based on nothing. It did everything you need to do to drive undiscerning young completists into a tizzy, yes, but I can also imagine that the subject matter also helped propel its early success: collectible monster toys were neat, but these ones were based on “real things”, which gave them an especially enticing angle. It was like one of those bestiaries I read, except in plastic form, which I guess some prefer.

Just like the Castlevania games (and there’s a more direct connection there that we’ll be getting to), Monster in My Pocket is a veritable monster party even in its first assortment of 48 figures, pulling from folklore, fairy tales, Cryptozoology, urban legends, and even more “modern” literature (Victorian times are still more modern than Greek mythology), getting all the mainstream headliners (vampires, werewolves, mummies, Frankenstein’s monster, the Phantom of the Opera, Medusa) but supplementing it with some more offbeat choices for the time (the Behemoth and Great Best of Revelation for all you Bible readers out there, Tengu, Windigo) and some truly deep cuts (the UK-specific goblin Redcap, the Aztec goddess Coatlicue, the Norse Jotun Troll, and the Catobleplas, a fixture of almost every book of mythical monsters I’ve ever read.) The people making these choices did some real research, pulling from the stories of very specific places and times rather than just relying on the ones that became Universal Monsters, and subsequent batches of new monsters (the series would total over 180 by its end, although later sets stopped using mythological creatures as their source material) would go even deeper, introducing kids to the Bishop Fish, the Nuckelavee (a human torso embedded in the back of a horse, and one of the most delightfully disturbing creatures out there), and the Elbow Witch of Ojibwa legend. Putting them all together in one big collection puts this diverse array of monsters on the same level, and thus elevates the less well-known ones simply by association (even if the point values are literally meant to determine which monsters were better.) When you go in to get Bigfoot or a griffin, and come out with Bloody Bones as well, you may just wonder, “so, what is this thing’s deal?”, providing an educational opportunity.

The line’s subject matter may have come from a previous generation of monster kids who remember hearing or reading about all these creatures, but it also fit very well with the tone of Western kids junk culture in the early nineties, where intentionally gross and ugly toys (which included plenty of tongue-in-cheek grotesque monster stuff) were all the rage among boys, or at least among marketers trying to get boys’ parents’ money. I’m sure an ad exec was sold on the idea that mythological monsters were “the original Ninja Turtles” (and yet, no kappas anywhere in the series), and in terms of design and packaging, Monster in My Pocket fit right in with those trends. Despite being based on thousands of years of human tradition, it was very easy to sell these monsters the same way they were selling Toxic Crusaders or Skeleton Warriors.

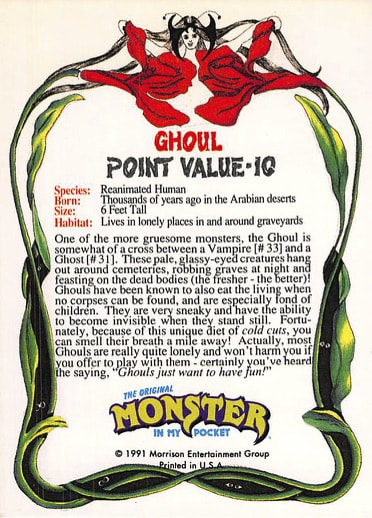

Another characteristic of the time: for little hunks of mass-produced unpainted soft plastic, the figures do have a lot of character—the dynamic poses and specific details of the sculpts do a lot to sell the monstrous nature of each one. Alongside the toys were sets of trading cards and stickers with painted art replicating the exact pose of the monsters, and those also tended to provide the monster’s description and origins as well. The sculpts and the (often pun and joke-filled) descriptions on the cards demonstrated how, despite pulling the names and ideas of the monsters straight from their sources, the people behind MiMP still came up with some “creative” interpretations of them—in some cases it’s kind of cute (the kraken’s buck teeth), sometimes its kind of clever (turning Jenny Haniver, the name for dried out skate carcasses sold as bogus monsters, into a skate-shaped creature with a scary face), and sometimes are so completely pulled out of nothing that most sources I looked up can’t even decide what the thing is supposed to be (“Karnak” is the name of a place, you yahoos.) Considering that these stories and creatures have been continuously reinterpreted since the beginning, MiMP is just keeping with tradition.

(While on the subject of the cards, they certainly make sure that Biblical creatures, or even ones pulled from demonology like the horse-headed Orobas, make absolutely no mention of their origins, keeping religion out of the equation—except that they still included Hindu deities like Kali, Ganesha, and Hanuman, and ended up having to alter or remove them when the people who still worship those deities complained about them being called “monsters.” The old monster books I read also sometimes included Ganesha, but these days, it’s probably not a good idea to be so blithe about figures from religions with over a billion followers.)

Make sure you emphasize those brand name products!

The thing that struck me the most while researching this post was just how ubiquitous these toys were for a time, with numerous tie-ins with restaurants and supermarket products (being fairly cheap to make probably made making them premiums pretty easy, and also seemingly makes completing the entire collection a pain in the ass) that were even more extensive overseas. As with most flash-in-the-pan toys of the era, Monster in My Pocket received all the other requisite tie-ins as well, including a short-lived Harvey comic (wasting the talents of Dwayne McDuffie, Gil Kane, and Ernie Colón), a one-off animated TV special that failed to spawn a series (but may spawn a blog post on this site, maybe), a music cassette (although I don’t know what to think of the Wikipedia entry partly crediting the music to “a person with the last name of Byrd”), and a pretty decent NES game from Konami, where a tiny vampire and Frankenstein fight other monsters in life-sized urban locales. To be fair, they were just giving out those kinds of things to anything that was vaguely successful at the time (I mean, Zen the Intergalatic Ninja got a Konami game), and given the generally abysmal attention spans of both kids and toy companies, this was not something that was ever going to last forever, even with an endless number of cool creatures to base toys on. After that initial period of boffo bucks, the whole thing petered out, and Matchbox went back to mainly making die-cast toy cars. There have been a few attempts to resurrect it over the last thirty(!) years (the 2006 version has some good quality sculpts, but I question the decision to steal the kraken design from Clash of the Titans), but nothing has stuck, even though it’s maybe the simplest concept in existence.

Although it was something I didn’t get to experience firsthand, I still find Monster in My Pocket a very interesting blip in monster culture history, especially in how it took some of the oldest monster stuff in existence and reframed it in a way to make it appealing to a jaded juvenile audience, and did so without even changing much about the source material. For a lot of kids, this was their introduction to an entire universe of monsters from all over the world, and one that can become even bigger and more interesting if they decided to take what the trading cards told them as a starting point. Even if it wasn’t something that kept going through the ages, I still wonder if MiMP helped usher in a new generation of monster kids and folklore fans, in the same way the creature feature TV packages and monster magazines created a legion of monster movie kids in decades prior…or how the fuzzy combination of things made me a fan in my childhood. These legends may not always be in the spotlight, but it has ways of coming back in new forms, and finding a new audience along the way—monsters, in or out of your pocket, are eternal.