We’re now in the merry Cormonth of Cormay, which is my extremely tortured way of saying that the rest of the month will be devoted to films by B-Movie King Roger Corman, who has directed 55 movies and produced hundreds more over a seven decade career (and while many of them are actually in the public domain, you can find the best quality versions on Shout Factory’s streaming site.) Corman is famous for many things, especially during the fifties and sixties: his economical (some might say tightfisted) budgets, speedy filmmaking, and an eye for talent that has given early breaks to some of the biggest names in Hollywood. Day the World Ended (which was apparently also the day proper grammar ended) is the first Sci-Fi/monster movie Corman directed solo, made in ten days (a record that he will quickly beat, as we will see), and embodies many of the common elements of Corman’s directorial efforts from this period, being efficient (with a small cast of actors and a limited number of locations), having a goofy-looking monster made (and played) by monster suit pioneer Paul Blaisdell, and being surprisingly effective for what it is.

Things start out clever, with a title card that tells us, among other things, “Our Story begins with…THE END!” (and yes, having planned on watching this movie over the past year, I’ve always known exactly what smart-ass topical things you’re thinking about right now, so cool it, pal), and then we’re immediately in a post-nuclear war America where most major cities have seemingly been wiped off the map. A very fifties sort of grimness, although I don’t think it was something that had been portrayed in a movie very often before this. A former military man, Jim, has been planning for that exact scenario since WWII, building a house and bunker in between a bunch of hills full of lead, and living there with his daughter Louise when the Big One finally occurs. They end up also letting in square-jawed geologist Rick (who coincidentally specialized in uranium), but are very soon joined by other survivors—morally bankrupt couple Tony and Ruby, stereotypical prospector Pete and his donkey Diablo (pronounced die-ah-blow, because white people), and a man seemingly dying from radiation exposure. Very quickly, we are given the dynamic between the cast, as Jim is reluctant to help anyone else because of their limited supplies, while Louise and Rick appeal to his basic humanity; meanwhile, Tony is constantly scheming to take over the group, and especially seems intent on claiming Louise, much to the dismay of Ruby. The focus is really on the tension and uncertainty of these clashing survivors navigating the new world, which is seemingly completely uninhabitable beyond the hills, with a worry that fallout in the atmosphere could rain down on them at any moment. Several of them seem to go back and forth on whether there’s any real future for any of them…and then a monster shows up, and that complicates things a bit.

(Interestingly, the actors playing Rick and Louise both have connections to one of the defining fifties monster movies, The Creature from the Black Lagoon—Richard Dennig was featured in the 1954 original, while Lori Nelson was in its 1955 sequel Revenge of the Creature, released a few months before this. Meanwhile, Mike Connors, who plays Tony, would become better known as TV’s Mannix, which I’m sure is something all of you reading this are eminently familiar with.)

There’s a certain seriousness in the character dynamics belied by the outlandish premise—while Rick and Louise mostly fill the traditional leading couple role you’d find in movies like this (although Louise’s late movie fall into fatalism gives her a more interesting character arc), you can definitely buy Jim’s realistic evaluation of the situation (and his planning for restarting the human race, although the fact that he needs his daughter and Rick to be married before having kids is a strange cultural holdover), and Tony is a top tier scumbag who sees the end as the opportunity to just grab whatever he wants. Pete is a goofy character whose main contribution to their little tribe is to brew moonshine, but there is something very sad about his determination to mine for gold even though it’s now worthless (he’s a prospector, gold is all he knows!) Probably the most well-developed character is the brassy Ruby, whose fairly believable reaction to the world ending is to the desperately try to keep up her old, fun-loving urban ways (she was very clearly a stripper, which seems fairly risque for a 1955 movie) until she breaks down in the middle of remembering one of her old acts, while her simultaneous anger and desperate need for Tony’s affection ends tragically, with a dummy thrown off the side of cliff. Since the monster stuff is used fairly sparingly, the survivors’ struggles are fairly important to keep the audience engaged, and the script by Lou Russoff (who wrote other Corman-directed movies in the fifties, including the infamous It Conquered The World) mines a lot more humanity from this scenario than I would have thought.

The more fantastical end of it has some intriguing ideas as well, even if they also fall into the realm of “radiation is magic” as much fifties Sci-Fi did. The guy suffering from exposure, with a gross scar on his face, is able to survive for weeks without food and water, and they figure out that he has been going out at night and hunting local wildlife that was likely also contaminated by fallout. Eventually, Jim tells Rick that during the war, he witnessed a bomb test that mutated several animals, which is shown using several simple (and kinda cute) illustrations—atomic energy apparently accelerated evolution in them to be able to survive exposure, which in this case means they grew inexplicable fangs and horns and their skin hardened. This appears to be what has happened to the irradiated guy to a lesser degree (and may potentially happen to them, leading to Ruby in particular becoming paranoid about signs of mutation), but when there are signs that the area around their house is being stalked by something less than human, they realize that he is only the tip of the iceberg. At one point, they ask that guy why he keeps coming back to them every day, he says that he has “an enemy”, which implies that he’s being bullied by the monster, which is an idea I find delightful. Later, they find an even more heavily-scarred survivor, and he basically tells them that the world over the hills has basically become Wacky Land, filled with bizarre forms of life, and while it’s nothing we ever actually get to see (because, you know, it’s got a Corman budget), the implications are more than enough.

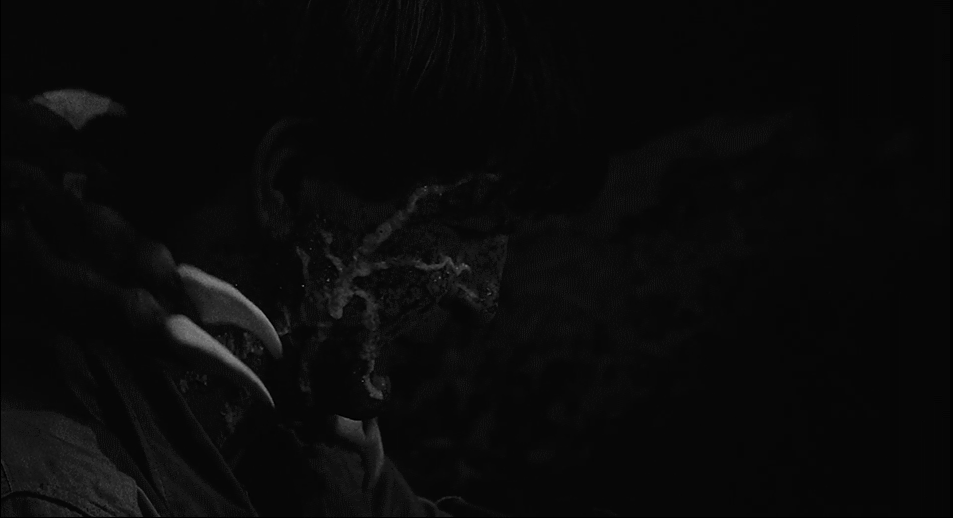

The monster itself, which looks like an alien Satan football mascot, doesn’t show up in full until very late in the movie, and aside from killing the irradiated guy and attempting to kidnap Louise (as per tradition), he doesn’t get to do much, really (I thought Tony would end up facing his karmic punishment through it, but what actually happens to him makes just as much sense in this story.) In fact, in the end he’s really more of a pathetic case—through him, we learn that the mutants created by radiation can only survive on equally irradiated subsistence, and are hurt by things like pure water. It’s Signs-level convenient, but it also has a point: the mutants are adapted for a “poisoned world”, as they say, and cannot live outside it. They didn’t ask to be that way, it’s just how the evolutionary cookie crumbles, and when pure rain shows up for the first time since the end, it immediately kills the monster, and seemingly cleans up the rest of the area (somehow? They clearly didn’t have a scientific advisor for this movie), providing a happy ending for Rick and Louise. There’s a vaguely religious angle to this, with Louise stating “Man created it…but God destroyed it”, but in general it’s there to make us feel insignificant in the face of nature, even after we manage to blow everything up.

One thing that was confusing about the ending: it seems like the connection between Louise and the monster was meant to be fairly direct (he “contacts” her throughout the movie, which is indicated by theremin sounds), and according to the plot synopses on other sites, you were supposed to find out that the alien Satan football mascot was actually the mutant form of her unnamed fiancee. You do get moments of her looking longingly at a photograph, and her reluctance to agree with her dad’s repopulation plan makes more sense in that light too, as well as her saying that she could hear the monster call her by name, but in the version I watched this was all fairly unclear. Apparently there were two minutes cut from the movie, so maybe this all just the vagaries of editing.

Also, the final title card says “THE BEGINNING”, which, you know what, that’s pretty awesome.

This might be one of those rare creature features where the monster is actually the least interesting part of the movie—albeit, not for lack of trying, and it’s classically goofy design is at least memorable (and is one in a long line of Blaisdell-made monsters in Roger Corman’s movies.) Probably for budget reasons, this focuses way more on the relatively small-scale character drama over the outlandish monster spectacle, which is definitely an interesting choice given that its a post-apocalypse story, and the movie benefits from it. Even if this Sci-Fi script doesn’t seem to understand how radiation or mutation (so, basically anything science-related) actually works, it does at least have some idea how people would act when put into the worst possible scenario, and even has some rather existential observations along the way. You don’t get the exact thrills you were expecting, but you still get them.