I’ve spent most of the last few posts in this series writing about how purveyors of pop culture make use of their histories—that is oftentimes the mainstream face of it, which can range from blatant nostalgia-grabs to even mildly subversive conversations between old and new. But as Philip José Farmer showed us, official sanction is not always needed, nor is it always preferred—while seeing established characters subvert their own meaning while under the auspices of some big money interest has a bold flavour, some points can only be made far away from the eyes of the IP holder. Self-parody has its time to shine—but parody from the outside can be meaner and more meaningful. There’s a history to this sort of bootleg storytelling, and through it we often get the most pertinent analysis of popular culture.

Comics is a medium where bootleg parodies have always existed in one form or another—for example, something like the Tijuana Bibles, pornographic parodies of popular comic strips, started in the 1920s. So, In Pictopia, a short comic originally published in December 1986,is part of a great tradition—but its background gives it a very specific place, time, and purpose. It was first seen in the Fantagraphics-published anthology Anything Goes, a book made specifically to help fund the publisher’s legal fees while it was being sued alongside writer Harlan Ellison by comics writer Michael Fleisher for libel and defamation of character, based on an interview in a 1980 issue of The Comics Journal between editor Gary Groth and Ellison (wherein the latter affectionately referred to Fleisher’s comics and prose work using terms like “bugfuck”, “derange-o”, and “certifiable.”) That lawsuit galumphed on from 1980 to 1986 and ultimately concluded on the side of the defendants—it is is a truly fascinating story, with many facets and a fallout that could be felt in the professional and fan spheres for decades, something where the overall pettiness soaking the whole endeavour ended up revealing much about the tensions that animate so much of the comics industry (you will see the Editor-in-Chief of Marvel Comics, under oath, casually state just how little the company regards its writers and artists, saying “I think that the fact that the writer’s name is on the material is a courtesy.”)

Poetically, this thirteen page comic story that was created specifically because of comics industry drama and is specifically about comics industry drama has, in the ensuing years, become attached to its own comics industry drama, something that is lightly reflected in the various recollections and essays printed in Fantagraphics’ 2021 reprint edition. However, the first thing that will tip you off to its backstory is the cover of the book, where the name of In Pictopia‘s writer is conspicuously absent. While primary artist Don Simpson (most well-known for his independent comic series Megaton Man, where he regularly satirizes comics and the comics industry) refers only to “The Author” in his flummoxed afterwards on the history of In Pictopia (an essay titled “Name-Dropping While Dropping the Name”), the credits in the comic reprinted therein is not so elusive—the writer is Alan Moore.

Needless to say, there is a long and complicated and very Alan Moore reason why this is yet another old comic where Moore refuses to let his association be put at the forefront, but let’s put all that aside. In Pictopia is an early example of something that Moore ended up doing all throughout his career, a deeply penetrating examination of a medium and genre, oftentimes pulling together a disparate group of characters reflecting the breadth of those mediums ( and yes, he acknowledges Philip José Farmer as an inspiration.) He’s written works in this vein through a multitude of milieus and styles*: in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen with the late Kevin O’Neill, in Lost Girls with Melinda Gebbie, in the various Top 10 series with Gene Ha and Zander Cannon, and in the H.P. Lovecraft comics Neonomicon and Providence with Jacen Burrows. It’s worth noting that In Pictopia has an interesting place in Moore’s comics timeline, being written and published at the same time as the first half of Watchmen—which is another work in that critical pastiche mode, maybe one of the most influential across all mediums. There’s several commonalities between those two comics especially, particularly the apocalyptic atmosphere found in both, and after reading them, you might possibly understand why Moore would swear off working for DC Comics before Watchmen was even finished.

In Pictopia focuses on Nocturno the Necromancer, a clear analog of Lee Falk’s comic strip character Mandrake the Magician—a character that, in 1934, helped define the modern idea of a costumed superhero, but by 1986 was a relic and an also-ran, despite what contemporaneous Saturday morning cartoons would have you believe—who shares a grubby apartment building (the “Prince Features Tenement”) with an analog of Little Nemo who suffers loud night terrors and a analog of Blondie who is forced to do unsavoury things to survive while her Dagwood is away “drying out.” Nocturno lives an aimless life, watching political caricatures have debates on television, and then wandering the streets of Pictopia—pretty literally a city of comics, with panels pasted across every surface and pages drifting in the breeze—visiting Funnytown, the ghetto where the cartoon animals (drawn by Mike Kazaleh) live, and then a bar packed full of cameos from recognizable and less recognizable comic strip characters (drawn by Peter Poplaski.), where he meets with his superhero friend Flexible Flynn, an elderly pastiche of Plastic Man (another character who was once popular and influential but had been left fallow by the mid-eighties.) There is a clear class system at play here—while older comics characters like Nocturno exist in faded world of monotone colours (an intentionally faded newsprint effect applied by colorist Erik Vincent) and the funny animals are left without work, superheroes are the only ones who “can afford to live in color.”

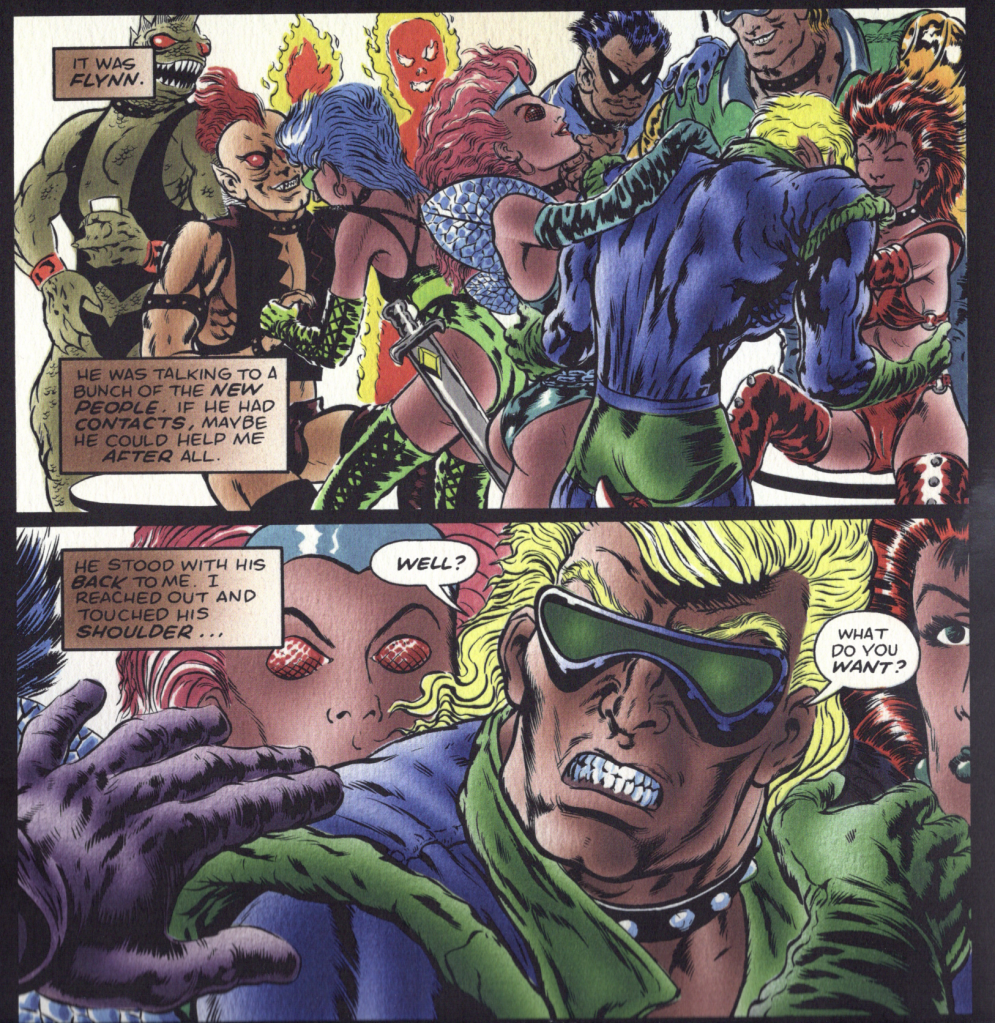

Standing at the bleak outskirts of Pictopia, Flynn notes how the horizon seems to be “getting closer”—later, at the bar, he tells Nocturno about denizens disappearing, and the sudden appearance of the “New People”, who represent modern superheroes. Nocturno later witnesses some of these New People—who Simpson draws as snarling, over-muscled, over-adorned grotesques—beating up a Goofy-esque dog man and laughing as he bounces back from injury as a cartoon character should (the narration tells us that some funny animals have been reduced to “[letting] you disfigure them for a buck.”) The world Nocturno knew quickly unravels as he flees from disturbing scene to disturbing scene, finding that Flexible Flynn has been rebooted into one of the New People (made to look “more realistic”), and then goes to Funnytown and finds it completely demolished, with a bulldozer operator telling him “This city’s changing, and some things just don’t fit continuity no more.”

There’s very clear meaning to these thirteen pages: the history and variety of comics are slowly being gentrified and then flattened by a single subcategory, characters replaced or deleted for not fitting into the modern mode. The new superheroes are a detached, monied class who have no respect for anything outside their genre, or even for their own forebears. The ills of the modern superhero—well, the modern superhero of 1986, although it’s certainly a style that we can still recognize today—are baked into the sinister nature of the New People: grittiness, “realism”, and a capitulation to “continuity” that strangles imagination—all things that were similarly lamented a few years later in the Grant Morrison-written Animal Man, a comparison that would likely incense Moore given the enmity between him and Morrison (that’s another very long story.) Still, that both seem to view a similar dark malaise gripping the genre is simply a sign of the times, when the increasingly violent and “serious” take on superheroes was in ascent, at least partially because of Moore-written comics like Watchmen. Now, the idea that Watchmen is solely responsible for coarsening the superhero comic for the next few decades (alongside Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns) has always been slightly overblown—Watchmen has an actual purpose behind its turn to realism, justifying its tone in a way that none of its imitators ever really tried—but In Pictopia even manages to show self-awareness on Moore’s part: when Nocturno walks in on a pair of scowling New People threatening not-Blondie for her immoral activities, one of them resembles Judge Dredd, the main star of the comic where Moore built his early reputation, and the other Vigilante, a second-rate Punisher knock-off that Moore had briefly written for in 1985.

For all that Animal Man was critical of the tics of modern superheroes and wistful for more innocent times, it was never as unsparing as Moore and Simpson are here. Nocturno’s narration is itself wistful for all the different kinds of comics that could exist, and the aesthetic eras they preserve just by existing—he describes Funnytown as a place where “Old radios…played nothing but thirties jazz!…”, where there are “No furnitureor cars later than 1950!…”, where there’s “No urban violence that wasn’t in some way amusing”, and whose inhabitants “…made just walking around seem like poetry. Every movement expressed so much.” Even in their dilapidated state, these characters bring Nocturno a sense of peace…until they are erased utterly and completely from the world of comics. The problem, as presented here, is not simply that the modern superhero comics are a misguided deviation from the stylized and imaginative world of, say, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man, but that they are a purely destructive force. Comic strips were once the dominant form of comics, creating numerous world-famous characters; funny animals were one of the most popular and viable genres, a tradition that started with Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck but veered off into its own thing; and once upon a time, the Golden Age superheroes could even co-exist with all of the other kinds of comics. By the end of the comic, modernity and money is shown to be erasing history and variety, further symbolized in Nocturno’s final narration describing the encroaching wasteland as “…a vast, creeping, industrial mass, wreathed in factory smoke and lit only by furnaces.”

The industry itself, represented by the increasingly joyless superhero sphere, is seen as hostile to the artistic possibilities of the medium, not content with sucking all the oxygen out of the room, but demanding that the sum total of comics be condensed into a singular kind of story and character. The idea that Marvel and DC’s output specifically is a creative black hole dragging down the entire the medium was, probably not coincidentally, the position taken by The Comics Journal in the eighties, who used every opportunity to lash out at those comics as assembly line crud whose vast numbers were entirely meant to crowd out all competition in stores (a well-documented tactic used by Marvel for decades.) Concurrently with all this was a growing independent comics movement that, in a sense, culminated in the Creator’s Bill of Rights in 1988, a document that was meant to encourage writers and artists to stand up for themselves in the face of the dominance of the small number of big comics publishers (whether it actually accomplished that task has been in debate since then.) This was something that was very much at the heart of the comics industry in the mid-eighties, and is neatly summarized by Moore and Simpson through In Pictopia‘s funny page Armageddon.

Now, with nearly thirty years hindsight, we know that things like comic strips and funny animals were not annihilated by dark, brooding superheroes—if they are not anymore important as mass cultural objects than they were in 1986, they have found ways to continue and even adapt to modern times (fans of older funny animal comics were, not surprisingly, crucial to the creation of the furry fandom.) The comics industry’s approach to its history can be strange, but reprints of the significant works referenced throughout In Pictopia keeps them in circulation to this day. I don’t think that means that the anxiety that Moore and Simpson depicted was not well-founded—I think it means it it was so well-founded that its sentiment did actually stir people to action, preserving comics history and non-superhero genre work, staving off the horizon for a few decades more.

But we have not seen the end of the deleterious forces In Pictopia described.

As I was with Animal Man, I was struck by how the arguments being presented here have recursively come back to the fan culture—not only did the grim ‘n’ gritty vigilante discussion continue on well into the nineties and beyond, but the last ten-plus-years of discourse about superhero movies specifically has made almost all the same arguments about the genre overtaking and flattening an entire medium (at a time when superheroes’ iron grip on mainstream comics readers has been mostly overtaken by manga, webcomics, and YA graphic novels.) It just keeps happening, and very few are equipped to notice just how cyclical it is. Writers like Moore have been part of the comics industry (one might even say wilfully trapped in it) long enough to know this cycle, and through reading them I have been cursed with the knowledge as well. Sometimes, seeing the industry trends and reading the arguments replicate themselves as they jump from movies to video games to television to whatever like a rampant zoonosis, I feel like Nocturno at the end of this comic, staring wide-eyed and delirious at the swirling desolation beyond the chain-link perimeter fence, knowing what is coming and being unable to stop it. In Pictopia is a product of its particular corner of culture, but it’s also a product of people who truly understand the natures of genre fiction, fandom, and the industry behind them.

*There was also the Image Comics project 1963, where Moore paid homage to early Marvel Comics alongside previous collaborators, including Don Simpson, and would have concluded with a crossover with the Image Comics characters themselves, which itself would have provided an interesting contrast between old and new…that is, if the conclusion had been published, which it was not, due to events that are still not entirely clear. This has also become a bone of contention with Simpson—so much so that, within the last year, he published his own “finale” to 1963 through Fantagraphics, a broadside against his former collaborator’s flakiness that even features the cast of In Pictopia.