The atomic monster category that was so profuse in the 1950s did not appear fully-formed, despite the timeliness of its inspiration: in the first major monster movie to use that device, The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, the nuclear bomb test that unleashes its titular dinosaur feels almost incidental, possibly even flippant when considered alongside the military triumphalism it ends on. That film was so successful that Warner Bros. was quick to follow it up the next year with more radiation-spawned giant monsters, this time going from stop motion dinosaurs to giant ant puppets (and in the process begot yet another category of monster movie that spanned the entire decade, the giant insect movie), but by comparison, Them! is a much more sober and startling take on the idea, despite what the excitable title and the promise of giant radioactive ants. While not coming off as some sort of didactic warning of what could happen now that Pandora’s box of atomic energy has been opened, it is much more serious-minded and engaged with the long-term effects of these things, and coming within a few months of Godzilla‘s premier in Japan in the same year, captures a period of more intelligent consideration of that new age than the wacky radioactive free-for-all that subsequently became the movie norm.

It is noted in the movie that the initial Project Manhattan tests in the New Mexico desert (where the early parts of the movie take place) were only nine years prior—it was not yet history then, but recent events, something that real people experienced firsthand…and something whose consequences were not even remotely fully determined. There was the impetus for this entire aesthetic trend: a completely new field of science and application of that science, and still so new that there remained numerous questions about just what its effects could be, all in the shadow of the horrifying realities of it that the world had already witnessed (though very few films outside of the original Godzilla ever really acknowledged that.) One of the underlying tensions of the post-war period, in the west specifically, was the optimistic pursuit of improvements and efficiencies through innovative science that popped up after (and likely due to) World War II, and if they were perhaps jumping into some of those things without studying all their potential side effects—Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, while focused on synthetic pesticides, is also a broad critique of the Atomic Age’s brash application of scientific innovation in the shadow of The Bomb. Before that, though, it’s interesting to see a movie like Them! suggest a similar sort of concern for the unexpected fallout of nuclear testing, taking place during (but not necessarily focused on) the simultaneous terrors of the Cold War, and in way less sensationalist than you might expect, what with the big ants and all.

A spate of mysterious disappearances and unusual property damage in the deserts of New Mexico (as portrayed by the deserts of Southern California) brings in the attention of a local police officer (James Whitmore) and an FBI agent (James Arness, star of Gunsmoke), who find, among other things, mysterious prints in the sand, sugar spilled throughout the crime scenes, and a little girl wandering the land in a stupor. They call for additional assistance, and are sent father-daughter myrmecologists Harold (Edmund Gwenn, Kris Kringle in the original Miracle on 34th Street) and Pat Medford (Joan Weldon), who seem to have figured everything out long before everyone else has and refuse to explain what they’re doing, much to the consternation of…everyone else. I guess it makes sense that they would want to be certain that they’re dealing with colossal ants before mentioning it, because could you imagine just saying the phrase “colossal ant” to someone out of the blue? Maybe if you lightened it up a bit by calling them “gi-ants.” Anyway, this of course, leads to one of the more famous scenes in the movie, when the scientists visit the girl in the hospital and expose her to the smell of formic acid, the kind used in the stings of ants and related species, and shocking her into screaming the title of the movie (this is set up earlier, when we see her take immediate notice of the distinct, unearthly sounds made by the ants in the desert.) It’s still a bit upsetting!

It’s not long before the cast, and the audience, gets to see their first gi-ant, and soon the entire colony is discovered, including the ants’ disposal heap of human remains (another surprisingly upsetting image.) The crew suss out the general behaviour of the ants—they only really leave their hole at night due to the heat—and then use that to help them find the best time to gas the entire tunnel with cyanide and then mop up the few survivors with flamethrowers. Although simple, the glimpse inside and outside of the anthill are atmospherically alien, and throughout the film there are many fairly elaborate sets that make full use of the giant ant props, one of the ways you know this was a big production and not a B-movie. Of course, said ant props are never fully realistic (nor do they have the fluid movement of Ray Harryhausen’s stop motion animation), but they properly give the movie scale and make it less reliant on potentially iffy optical effects. Director Gordon Dogulas (who, among many other things, directed some of the most well-known Our Gang shorts—it’s true!) keeps the whole movie fairly grounded, and makes consistently effective use of both the wild and urban settings, where claustrophobic tunnels (both natural and human-built) and wide open areas carry the same level of menace. This movie was originally going to be filmed in colour and in 3D, but that was dropped just before filming began (in some versions, the movie’s title is still evocatively crimson-coloured)—I was surprised that there weren’t more really obviously-meant-for-3D shots in the movie.

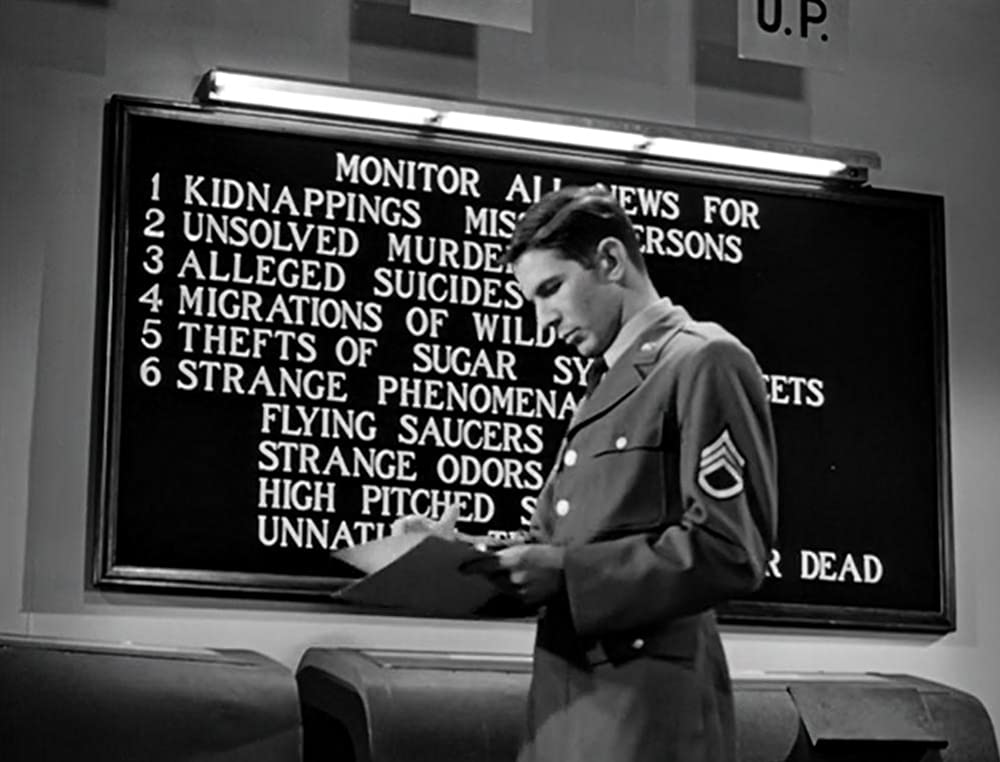

Unfortunately for homo sapiens, we see that a few new queens and drones (those are male ants, by the way) had hatched and flown the coop before the extermination, so it then becomes a game of cross-country investigation as our heroes try to prevent the queens from starting more colonies across the US, while also keeping the whole thing under wraps to prevent nationwide panic (we never get to see a full-grown queen ant, which would likely have been too big and elaborate a thing to construct in 1954.) This involves interviewing some enjoyable colourful characters, including a pilot (future Davy Crockett Fess Parker) who was institutionalized after telling people he saw “ant-shaped flying saucers” (it’s worth remember that UFO mania was also pretty big at that time, also very evident in the era’s monster movies)—in order to keep him from spreading the idea around, our heroes tell the doctors to keep him locked up, which one of the many authoritative actions they take in the second half of the movie to control the situation, which also includes monitoring all news wire services for potential ant sightings (a scene that includes a brief appearance by a young Leonard Nimoy) and, after discovering ants there, putting the entire city of Los Angeles under Martial Law. These things seem pretty harsh, but they are a far more logical reaction to the fantasy situation than you’d see in a movie like this (they bother to explain how the establishing of ant colonies works and extrapolate from there for further tension), and it’s clear that the screenplay is a lot more considered than a giant insect movie usually is. Helping that, the characters aren’t deep, but are played with some degree of personality so they don’t come off as boring, and Gwenn specifically gets several comedy moments (like him not knowing how to properly communicate with the helicopter’s radio.) Screenwriter George Worthing Yates was a major contributor to the fifties monster movie boom, writing Them! alongside the Harryhausen effects projects It Came From Beneath the Sea and Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, and even Bert I. Gordon non-classics like The Amazing Colossal Man. He even contributed to the American version of King Kong vs. Godzilla! Clearly, he was someone who had a way with giant monster movies.

The finale takes place in the Los Angeles River’s storm drain system, a great setting for a monster hideout, and this movie’s use of it ends up being referenced in later movies like It’s Alive (you can also see a lot of inspiration from this movie in Aliens, including the eccentric drunk saying a version of “they mostly come at night.”) It is a lot of watching soldiers drive through tunnels and blast ants with flamethrowers (another important note: this movie makes frequent use of the famous Wilhelm Scream, and while Gordon Douglas didn’t make the first movie to use it, he did direct the movie from which it eventually derived its name, 1953’s The Charge At Feather River), but the scope and atmosphere of the scenes elevate them above what could be a standard finale. Even so, after not pulling punches for much of the movie, having them not only save a pair of children trapped in the tunnels, but also having their mother outside to listen as it happens (despite the whole martial law/curfew thing) is a bit more of the ol’ Hollywood sentiment—on the other hand, they already showed one child being traumatized for life, so maybe they just wanted to balance it out a bit.

Even though we watch as the last of the radioactive ants is dealt with, this is not a movie that ends with a clean, status quo-affirming conclusion. The question is broached directly: if the very first atomic tests produced something like this (which took almost a decade for the world to discover), what about all the other tests that had been done since? As Dr. Medford says in the closing monologue “When man entered the Atomic Age, he opened the door into a new world…what we eventually find in that world, nobody can predict”, laying bare all the fears that would resurface again and again in monster movies throughout the fifties—what people found in the new world, as it turns out, were a lot more giant insects and other sorts of radioactive abominations. Although the meddling in God’s domain theme is a cliche in science fiction, this feels less like scolding moralism or doomsday pessimism and more a basic acknowledgement of cause and effect, which is not something that is always acknowledged (although this still feels a bit removed from the actual human cost as compared to the Japanese giant monster movies.) Them!‘s influence is not just seen in the massive bugs to follow, or the nuclear paranoia, but in the much broader realization that we exist within a natural world that will invariably respond to what we do.